On Potatoes: Spud Science

No matter who or where you are, nothing is at home on your plate quite like a potato. These carby lumps compose stereotypes from Idaho to Ireland and compose signature dishes ranging from Canadian Poutine to Indian (or African) Samosas. Even the simple idea of cutting them up and frying has meaningful, regional flair the world around. Belgian frites, English chips, and thin American fries might seem interchangeable, but their exact methods, temperatures, textures, and accompaniments are proving to be some of our most enduring food rituals.

It’s therefore worth a deeper look at what makes potatoes perform as they do in different preparations. We probably know that perfect mashed potatoes, french fries, or potato salad start from different tubers, but here, we’ll dive into why potatoes vary as they do and what types belong in which dishes.

Starting with Starch

Along with the other staple crops like rice or corn which helped humans start to stay put, potatoes are a plant’s way of concentrating nutrients. But while the original edible bits of corn, rice, and wheat evolved to help those plants spread, potatoes evolved to help the plant survive. Tubers like potatoes are storehouses for the plant, staying in the cool, steady-temperature, dark soil to power growth aboveground.

Let’s crash Biology 101 together. Plants create sugar (glucose) through photosynthesis for energy. Some of the sugar is stashed away as starch for later use (otherwise, it oxidizes and becomes unusable). That starch is a long chain molecule with a great cellular shelf life, which can also last long enough for storage in our pantries.

How do we explain the difference between different high-starch foods like sticky rice and potatoes? The answer is the types of starch in the food. Some plants (rice) lend a stickiness to food, while others (potatoes) add fluffiness. Potatoes are often higher in the starch amylose, which is a longer, straighter starch that remains angular and crystallizes readily. Amylopectin, the sticky type of starch more prevalent in sticky rice, is a jumbled branching molecule, which forms a cohesive and gooey gel.

Amylose

Amylopectin

Amylopectin-rich foods

Short-grain rice

Cassava

Yams

Tapioca

Amylose-rich foods

Potatoes

Banana peels

Beans

Long-grain rice

While this crash course in photosynthesis and starch structure isn’t the sexiest of topics, it does help orient us around why potatoes behave as they do: concentrated storage of amylose starch.

Mealy vs Waxy

Now, what accounts for the diversity among potato varieties? The components of potatoes are pretty consistent: mostly water (60-70%), starch (10-15%), sugars (2%), protein (2%), and minerals / fiber (2%).

However, the small wiggle room with each of these percentages has a tremendous impact on the texture and usage of the potato. The potato variety is the main driver of this, but the age of the potato is also impactful, especially for starch content. Older potatoes have had more time to store all those sugars and convert them into starch. Older potatoes also have more time to grow big, and have less water in their cells.

Through this you can start to see a web of connected factors that influence the starch, sugar, and moisture of the potato. These qualities have a tremendous impact on flavor. Younger, smaller potatoes are sweeter and wetter with less starch, so cooking them brings out sweetness with a moist, creamy interior. Older, larger potatoes are starchier and drier with less sugar, so cooking them exposes a fluffier starchy texture as the cells burst under heat.

At last, we start to arrive at the great potato spectrum, a loose jumble of traits it’s helpful to draw a culinary binary around. The two poles are waxy and mealy. The potato people didn’t run those labels past marketing, but at least it’s clear! Let’s explore.

Waxy

Mealy

High sugar

Low starch

High moisture

Younger (often)

Smaller (often)

Low sugar

High starch

Low moisture

Older (often)

Larger (often)

Now, what does this mean for the home cook? A few notes:

Creamy

Moist

Thin skin

Holds shape

Best for: boiling, roasting, whole preparations.

Examples: new, red-skinned.

Fluffy

Dry

Unpleasant skin

Breaks down into paste

Best for: mashing (less agitation required), frying (don’t burn).

Examples: russets, blue / purple, fingerlings.

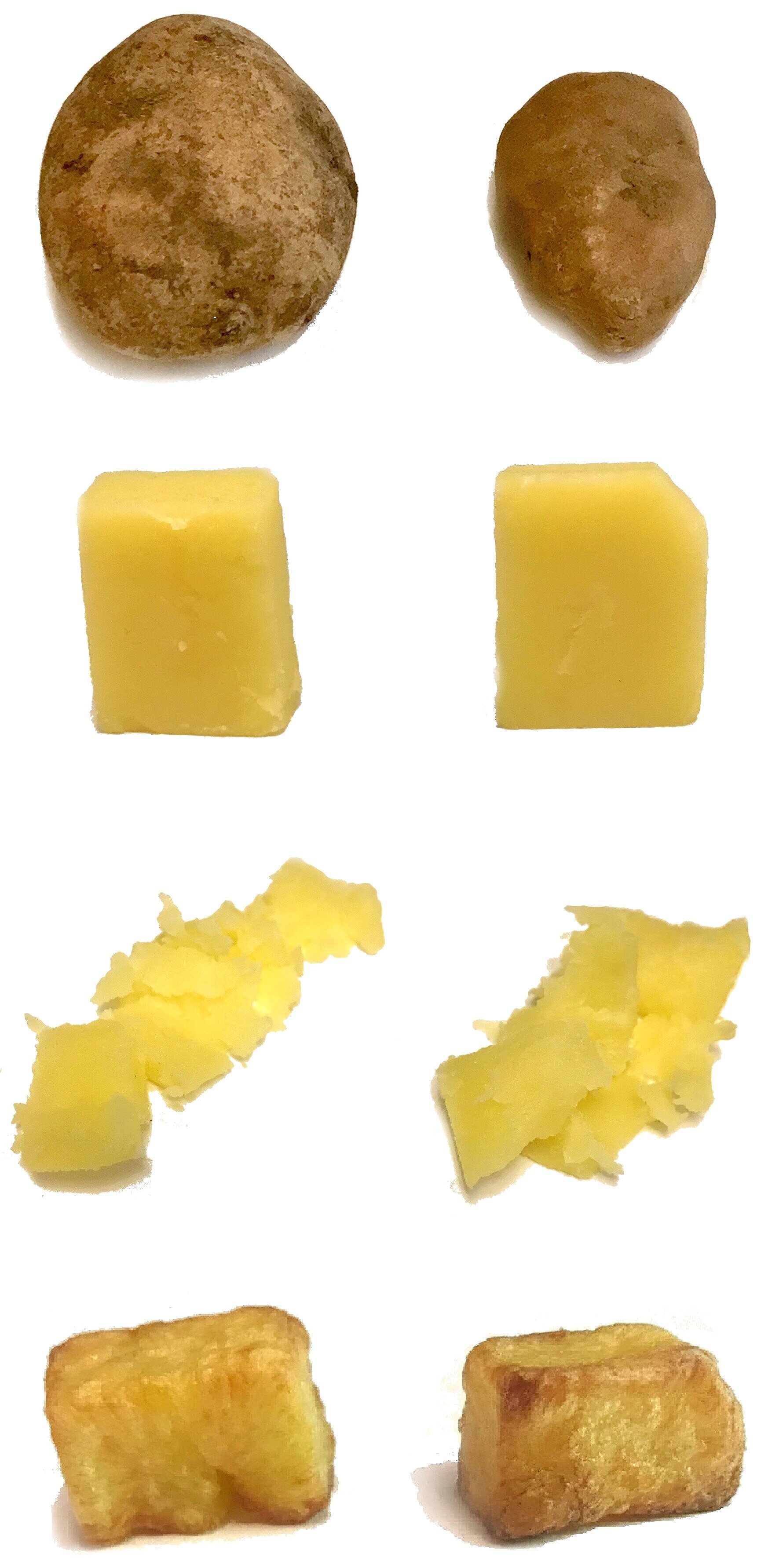

I did a quick test to confirm this, simmering a similar-sized piece of a mealy and waxy potato, crushing half for texture, and baking the other half until crisp. It’s tricky to see in the photo, but you can just see how the mealy potato broke down easily into fluff from the cell, while the waxy potato ‘cracked’ into distinct, wetter chunks.

For the baked piece (I brushed the pieces with oil first), the waxy potato browned faster due to the higher sugar content and was unbelievably creamy. However, the starchy potato was much more appetizing when baked: fluffy and light, this single small bite fulfilled a longing for McDonald’s fries I didn’t know I had.

Mealy

Waxy

Let’s get cooking

Now that we’ve nailed down this spectrum, here are some well-known preparations and a few recommended recipes for each type:

Mealy

Potato Gnocchi: one of my favorite dinner party recipes –– festive, filling, cheap, and best made ahead. Perfect gnocchi balance bite and fluff. Overworking the potato also condenses the fluff and forms a dense, chewy chunk of boiled dough. You want to maintain as much control of the moisture as possible (by adding eggs), so it’s best to bake the potatoes so they enter the dough fluffy and dry (the recipe I linked here is otherwise great). You can also bake a beet with the potatoes, blend, and mix that in for a lovely pink, earthy gnocchi. Toss the gnocchi with a simple creamy sauce with peas or asparagus, bacon, and loads of black pepper.

Crispiest Potatoes: this brilliant recipe breaks down the outsides of mealy potato pieces to form a starchy, fatty, salty slurry which then bakes into a crispy and creamy shell around the potato.

Mashed Potatoes: if you’re chasing maximum fluffiness in your potatoes, you’re really trying to agitate the starch as little as possible. It’s easier to do this with potato varietals that break apart with limited mashing so you can simply run them through a ricer and gently mix with enriching ingredients like butter. It’s also best to rinse the cut potatoes first to do away with any loose starch that can create a gluey mess.

German Potato Salad: the Swabian potato salad that comes to mind here takes an acidic sauce and tosses it with sliced, mealy potatoes to form a thick, starchy coating for the salad. For a look into the German culinary psyche, scroll through the “Kartoffelsalat” search results on the German cooking forum chefkoch, and you’ll see a relatively consistent cascade of yellow, glistening potatoes nach Omas Art.

Waxy

Spanish Tortilla: lightly fried slices of waxy potatoes are combined with eggs and (sometimes) onions into a frittata, cooked over the stove and flipped as the eggs start to set. Here, you want a bite of the potato to come through the soft scrambled egg.

Boiled Potatoes: a perfect, simple side, boiled new potatoes are at home beside a range of heavy German and French dishes, like Beelitzer asparagus with hollandaise (rich, funky, acidic) or rouladen with red cabbage (rich, funky, acidic).

American Potato Salad: boiled and sliced, the toothiness and creaminess of a waxy potato is accentuated by the creaminess of its mayonaisse-based dressing. While potluck and cookout foods might get scorned by the snobbier among us, there’s no denying that creamy but substantial potatoes, a few pops of crunch from onion or celery, and sharp flavors from mustard or vinegar make this a beautiful side.